Ever wondered how the world's leading powers are shaping the future of AI?

This report provides a comprehensive side-by-side comparison of these two influential plans. Its purpose is to dissect and highlight the significant differences in their underlying political philosophies, decision-making processes, and distinct approaches to fostering AI innovation, building infrastructure, managing data, developing talent, and engaging internationally. By drawing out these key divergences, the analysis aims to offer a nuanced understanding of the transatlantic AI landscape and its broader implications.

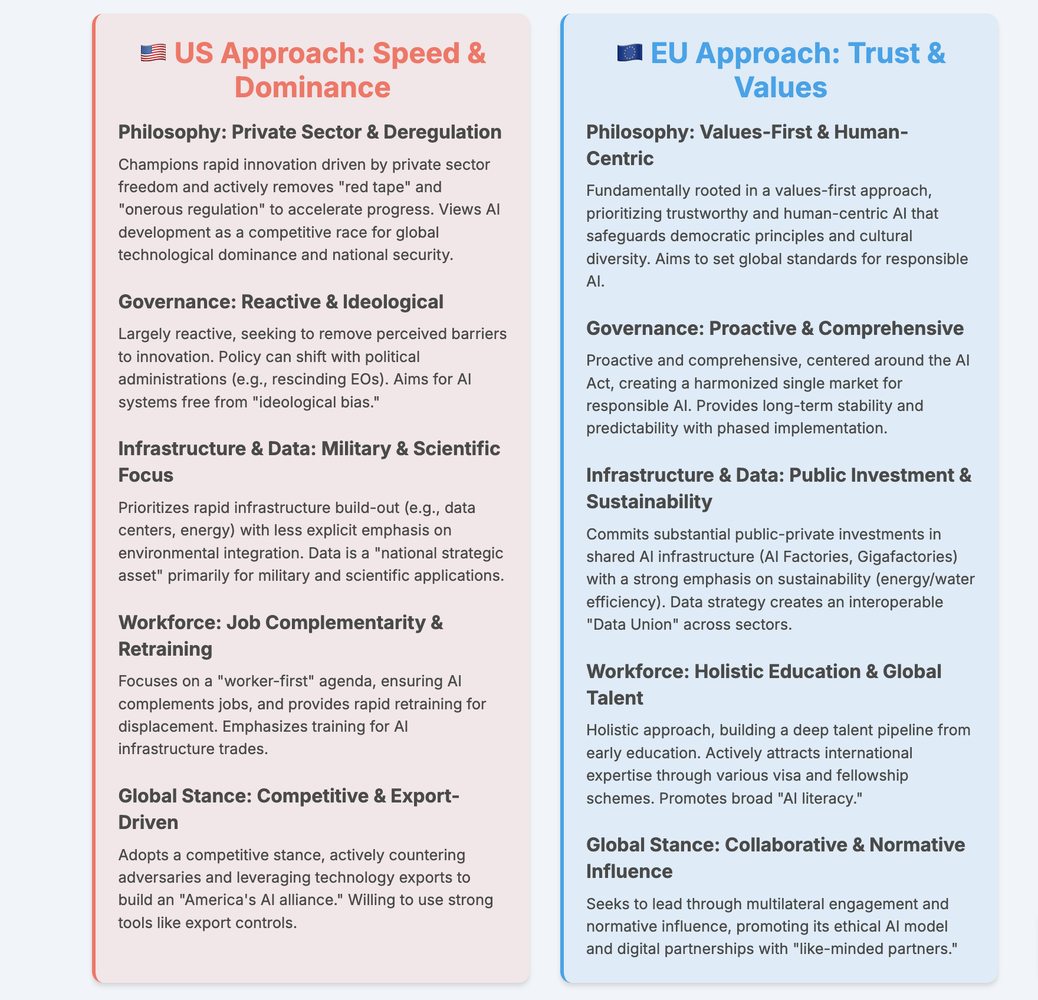

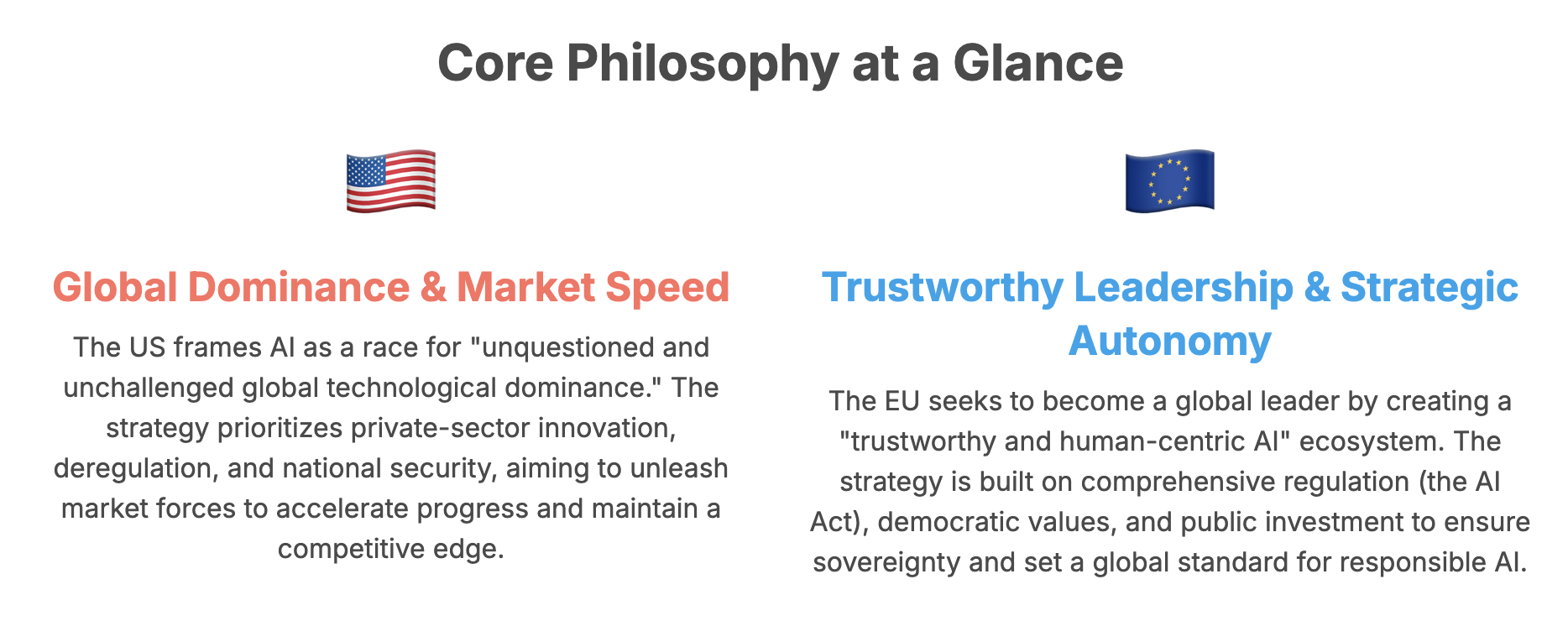

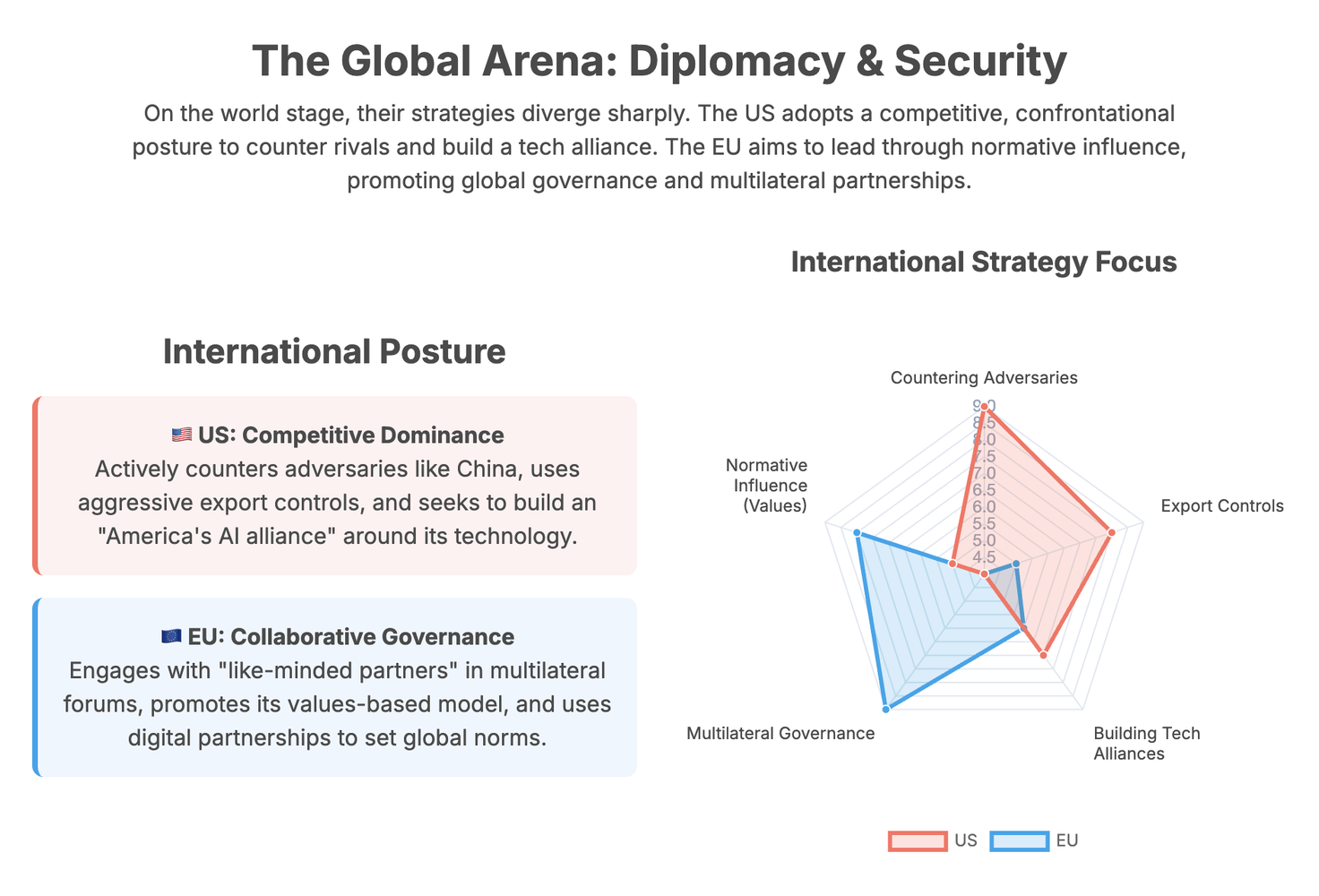

The United States and the European Union, while both aspiring to global leadership in Artificial Intelligence, articulate fundamentally different approaches rooted in distinct political philosophies, decision-making paradigms, and strategic priorities. The US "America's AI Action Plan" champions a deregulatory, private-sector-led model focused on achieving global technological dominance and national security, often framing AI development as a competitive race. Conversely, the EU's "AI Continent Action Plan" prioritizes a values-centric, human-centric AI ecosystem built on comprehensive regulation, strategic autonomy, and collaborative governance, aiming to set global standards for trustworthy AI. These contrasting visions manifest across their strategies for innovation, infrastructure, data governance, workforce development, and international diplomacy, leading to significant divergences in their policy tools and anticipated outcomes.

The advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) represents a transformative technological frontier, poised to reshape global economic landscapes, national security paradigms, and societal structures. As nations and blocs vie for influence and advantage in this rapidly evolving domain, their strategic approaches to AI development and governance are becoming increasingly defined. The United States, through its "America's AI Action Plan," and the European Union, with its "AI Continent Action Plan," stand out as two prominent entities charting distinct courses for their AI futures.

Core Philosophy at a Glance

Overarching Political and Ideological Drivers

US Perspective: Global Dominance and Private-Sector Innovation

The "America's AI Action Plan" is explicitly anchored in an assertive pursuit of global technological supremacy. The document unequivocally states that the United States is in a "race to achieve global dominance" in AI, positing this as a "national security imperative" to secure "unquestioned and unchallenged global technological dominance". This competitive framing suggests that whoever commands the largest AI ecosystem will dictate global standards and reap extensive economic and military advantages. The plan envisions AI ushering in a "new golden age of human flourishing, economic competitiveness, and national security for the American people," encompassing industrial, information, and artistic revolutions simultaneously.

A core tenet of the US strategy is the belief in private-sector-led innovation. The federal government's role is primarily to "create the conditions where private-sector-led innovation can flourish" by dismantling "unnecessary regulatory barriers" and "red tape". This includes an explicit rejection of "radical climate dogma and bureaucratic red tape" to facilitate infrastructure development, encapsulated in the mantra "Build, Baby, Build!". The plan also emphasizes a "worker-first AI agenda," aiming to ensure that AI complements American workers rather than replacing them, thereby increasing the standard of living for all citizens.1 Ideologically, the US plan mandates that AI systems "must be free from ideological bias and be designed to pursue objective truth rather than social engineering agendas," while also protecting free speech and American values.Vigilance against misuse or theft of advanced technologies by malicious actors is another driving force.

European Perspective: Trustworthy AI, Values, and Strategic Autonomy

The European Union's "AI Continent Action Plan" articulates an ambition to become a "global leader" in AI, but defines this leadership through a distinctive, values-centric lens.The EU seeks to shape AI development in a manner that simultaneously "enhances our competitiveness, safeguards and advances our democratic values and protects our cultural diversity". The concept of "trustworthy and human centric AI" is central to this vision, viewed as crucial for both economic growth and the preservation of fundamental rights and principles.

The EU intends to leverage its inherent strengths, including its large single market governed by a "single set of safety rules across the EU," notably the recently adopted AI Act, which ensures AI aligns with EU values. The plan also highlights Europe's high-quality research, skilled professionals, thriving startup ecosystem, and industrial expertise as key assets. A significant driver is the pursuit of "strategic autonomy in scientific progress and critical industrial sectors," aiming to "reduce dependencies on critical technologies and and strengthen sovereignty in cutting edge semiconductors". This focus on sovereignty is informed by lessons learned from the COVID crisis and recent geopolitical developments. The EU’s commitment to "open innovation" is also a notable aspect of its strategy. Furthermore, the protection of Europe's linguistic and cultural diversity is a specific objective, exemplified by initiatives like the Alliance for Language Technologies (ALT-EDIC).

Key Differences in Political Philosophy

A fundamental divergence emerges in their philosophies regarding global AI competition. The United States explicitly frames its AI ambitions as a "race to achieve global dominance" and a "national security imperative" to maintain "unquestioned and unchallenged global technological dominance". This assertive language positions the US in a direct competitive stance against "global competitors," suggesting a zero-sum view where technological supremacy is paramount. This approach shapes its international engagement, prioritizing bilateral alliances and potentially leading to strategies focused on technological denial to adversaries. Conversely, the European Union, while also seeking to become a "global leader" in AI, defines its leadership through the lens of "trustworthy and human-centric AI" that "safeguards and advances our democratic values and protects our cultural diversity". This indicates a different form of global leadership, one rooted in normative influence and multilateral collaboration with like-minded partners, emphasizing shared principles over pure competitive supremacy. This distinction will inevitably influence their respective international engagement strategies, potentially leading to friction or opportunities for selective cooperation in the evolving global AI landscape.

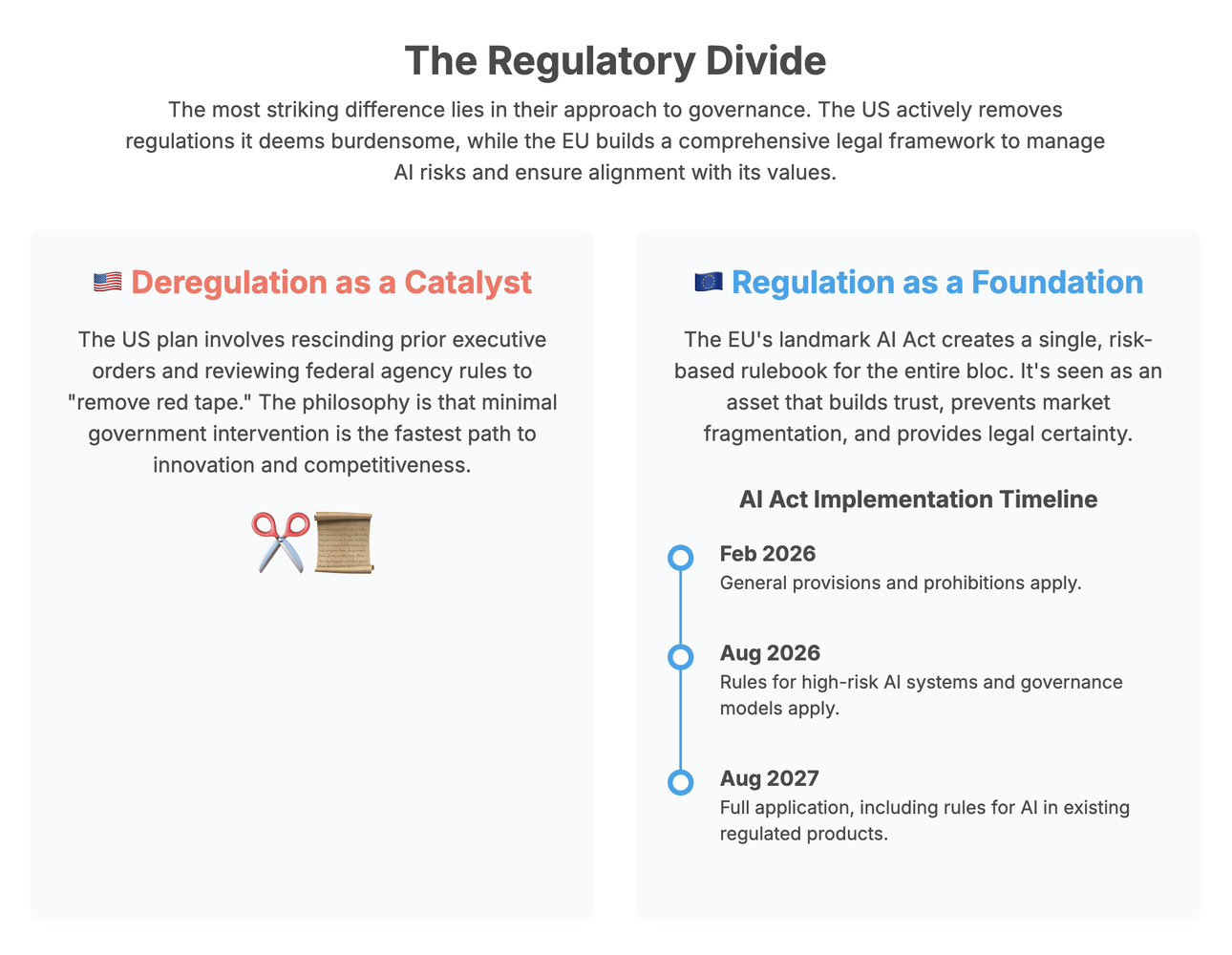

Another significant difference lies in their approach to regulation. The US actively promotes deregulation and rescinds previous administrative actions, such as Executive Order 14110 , framing it as essential for private sector flourishing and winning the AI race. This suggests a belief that less government intervention inherently accelerates innovation and competitiveness. The European Union, however, views its "single set of safety rules" through the AI Act as an asset, preventing market fragmentation and enhancing trust and security in AI technologies. This implies that for the EU, regulation is not a hindrance but a necessary foundation for a well-functioning, trustworthy market that attracts investment and fosters innovation aligned with its values. This fundamental difference in regulatory philosophy will likely create friction in transatlantic AI policy discussions, with the US advocating for minimal government oversight and the EU pushing for robust governance frameworks.

Furthermore, a distinction can be drawn in the primary drivers for AI development. The US explicitly states AI is a "national security imperative" and frequently mentions military and intelligence community applications.1 This indicates that security concerns are a direct, top-level driver for AI policy. The EU, while also concerned with security (e.g., "secure value chains"), frames its approach more broadly around "strategic autonomy" to reduce dependencies and strengthen sovereignty across critical industrial sectors. This suggests a more comprehensive, long-term geopolitical goal beyond immediate military advantage, focusing on resilience and self-reliance across its economy. The US might prioritize rapid deployment of AI for defense applications, potentially leading to different ethical considerations for military AI, while the EU's strategic autonomy goal could lead to greater investment in domestic capabilities across civilian and dual-use technologies.

Finally, the ideological underpinnings of AI content and application diverge. The US plan's directive to ensure AI "protects Free Speech and American Values" and is "free from ideological bias and be designed to pursue objective truth rather than social engineering agendas" reflects a concern about the ideological leanings of AI outputs, potentially influenced by domestic political debates or a critique of state-controlled AI systems in other nations. The EU's explicit commitment to "protecting cultural diversity" is a unique European value, reflecting its multilingual and multicultural composition, which directly influences its data strategies, such as the Alliance for Language Technologies (ALT-EDIC). These ideological stances will profoundly shape the development and deployment of AI applications. The US might prioritize AI models that are perceived as "neutral" or aligned with specific political interpretations of truth, potentially leading to content moderation debates. The EU's emphasis on cultural diversity will likely result in AI systems designed to support multilingualism and diverse cultural expressions, potentially influencing global standards for inclusive AI.

Approaches to Decision-Making and Governance

US Model: Deregulatory, Agency-Led, and Ideological Alignment

The US approach to AI governance is characterized by a strong emphasis on deregulation and a decentralized, agency-led implementation. The administration has taken decisive steps to "Remove Red Tape and Onerous Regulation", including rescinding the previous administration's Executive Order 14110 on AI, which was seen as foreshadowing an "onerous regulatory regime".1 Federal agencies, led by the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), are directed to identify, revise, or repeal regulations that unnecessarily hinder AI development or deployment.1 This includes reviewing Federal Trade Commission (FTC) investigations to ensure they do not "unduly burden Al innovation".

The US plan also ties federal funding decisions to a state's AI regulatory climate, potentially limiting funds to states with burdensome AI regulations. A notable policy action dictates that the NIST AI Risk Management Framework be revised to "eliminate references to misinformation, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, and climate change".Furthermore, federal procurement guidelines are updated to ensure that government contracts only go to large language model (LLM) developers whose systems are "objective and free from top-down ideological bias".Interagency coordination is formalized through the Chief Artificial Intelligence Officer Council (CAIOC), serving as the primary venue for collaboration on AI adoption across federal entities.

European Model: Comprehensive, Risk-Based Regulation, and Collaborative Harmonization

The EU's governance model for AI is defined by its comprehensive and proactive regulatory framework, primarily the "recently adopted Al Act".This Act establishes "one single set of safety rules across the EU," aiming to prevent market fragmentation and ensure AI is trustworthy and aligned with EU values. The AI Act employs a "targeted and risk-based approach," imposing requirements specifically on "high-risk AI applications". Its implementation is phased, having entered into force on August 1, 2024, with full application expected by August 2, 2027.

To facilitate a smooth and predictable application of the AI Act, the European Commission is launching the "AI Act Service Desk," intended as a central information hub offering "straightforward and free access to information and guidance" for stakeholders, including practical advice and self-assessment tools.National AI regulatory sandboxes are being established in Member States, expected to be operational by August 2026, allowing for controlled testing of AI systems. The "AI Pact" encourages stakeholders to engage directly with the AI Office, sharing experiences in implementing AI Act measures.The Commission continuously provides guidance through implementing delegated acts, guidelines, and co-regulatory instruments such as standards development and a Code of Practice on general-purpose AI.The AI Board, composed of Member States, plays a crucial role in assisting with the consistent application of the AI Act across the Union.The EU emphasizes gaining practical experience with these new rules before considering any further legislation on AI.

Key Differences in Governance Philosophy

A significant difference lies in the regulatory stability and political influence on AI policy. The US approach is characterized by reactive deregulation, as evidenced by the explicit mention of "rescinding Biden Executive Order 14110" and reviewing "FTC investigations commenced under the previous administration".This suggests that AI policy can be significantly altered with changes in political administration, potentially leading to instability and uncertainty for businesses. In contrast, the EU's AI Act is a comprehensive legislative act, representing a multi-year effort involving all Member States. While its implementation is phased, the legislative foundation provides greater long-term stability and predictability across the bloc. This difference in regulatory stability could influence investment decisions and the long-term planning of AI companies, with some potentially preferring the regulatory clarity (even if strict) of the EU over the potential for rapid policy shifts in the US, or vice versa, depending on their risk appetite and business model. It also highlights a fundamental difference in political systems: executive order-driven policy in the US versus multi-stakeholder legislative consensus in the EU.

Another core philosophical divergence concerns the role of regulation itself. The US plan consistently portrays regulation as "onerous" and a "barrier" to innovation. The underlying assumption is that less regulation automatically equates to more innovation. Conversely, the EU, while implementing a stringent AI Act, simultaneously launches initiatives like the "AI Act Service Desk" and "AI regulatory sandboxes".This demonstrates a belief that well-supported regulation can facilitate compliance, build trust, and ultimately enable responsible innovation by providing clear rules and a level playing field. This represents a core philosophical divergence on the role of government in technological advancement. The US sees government's role as primarily removing obstacles, while the EU sees it as actively shaping the market through regulation to ensure desired societal outcomes, believing that trust and safety are prerequisites for widespread adoption and long-term economic benefit. This could lead to different types of AI innovation flourishing in each region: rapid, potentially riskier, market-driven innovation in the US versus more cautious, ethically aligned, and standardized innovation in the EU.

Finally, the approach to AI content and ideological alignment differs. The US plan's directive to revise the NIST AI Risk Management Framework to "eliminate references to misinformation, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, and climate change" and to ensure federal procurement contracts only with LLM developers whose systems are "objective and free from top-down ideological bias" indicates a governmental attempt to shape AI outputs based on a specific political ideology. The EU's AI Act, while values-driven, focuses on a "risk-based approach" to mitigate harm and ensure fundamental rights, without explicitly dictating ideological content. This could lead to a divergence in the types of AI systems developed and adopted in each region, with the US potentially favoring systems that align with its stated ideological preferences, while the EU prioritizes systems that are transparent, fair, and accountable, regardless of specific political leanings, as long as they mitigate identified risks.

Core Strategies for Fostering AI Innovation and Research

US Strategies: Private-Sector Enablement and Targeted Federal Investment

The US strategy for fostering AI innovation is fundamentally rooted in empowering the private sector. The federal government aims to "create the conditions where private-sector-led innovation can flourish" by removing regulatory burdens. A key tenet is the encouragement of "Open-Source and Open-Weight Al" models, recognized for their "unique value for innovation" for startups and academics, and their "geostrategic value".The plan seeks to improve the financial market for large-scale computing power, thereby ensuring access for startups and academics, and partners with leading technology companies to increase the research community's access to private sector resources as part of the National AI Research Resource (NAIRR) pilot.

Federal investments are guided by a new "National Al Research and Development (R&D) Strategic Plan".These investments are targeted at "fundamental advancements in Al interpretability, control, and robustness" , particularly for high-stakes national security applications. The US also aims to build an "Al Evaluations Ecosystem" to assess the performance and reliability of AI systems, publishing guidelines and investing in AI testbeds for real-world piloting. Efforts are also directed at enabling AI adoption through "regulatory sandboxes or Al Centers of Excellence" for rapid deployment and testing, and domain-specific initiatives in sectors like healthcare, energy, and agriculture to develop national standards and measure productivity gains.Furthermore, the plan includes investing in AI-enabled science through automated cloud-enabled labs, supporting Focused-Research Organizations, and incentivizing the public release of high-quality scientific datasets.

European Strategies: Public Infrastructure, Sectoral Adoption, and Foundational Research

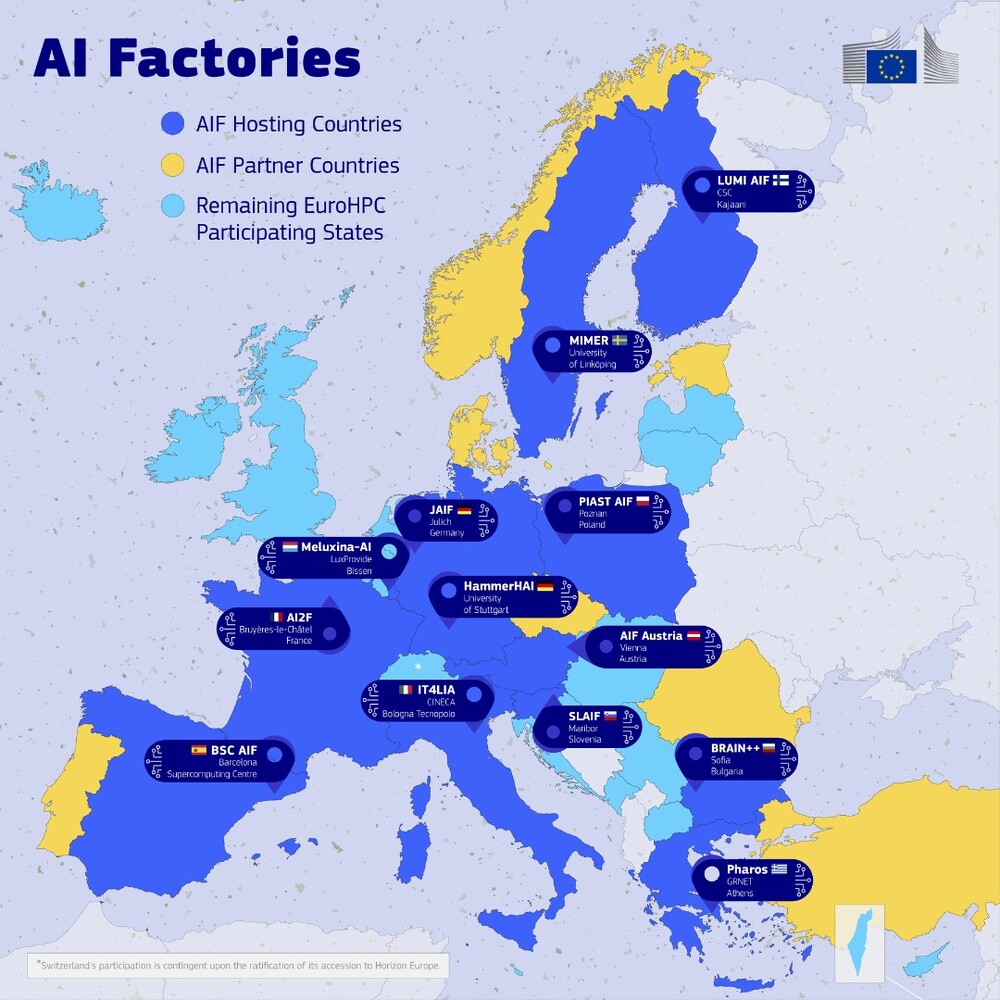

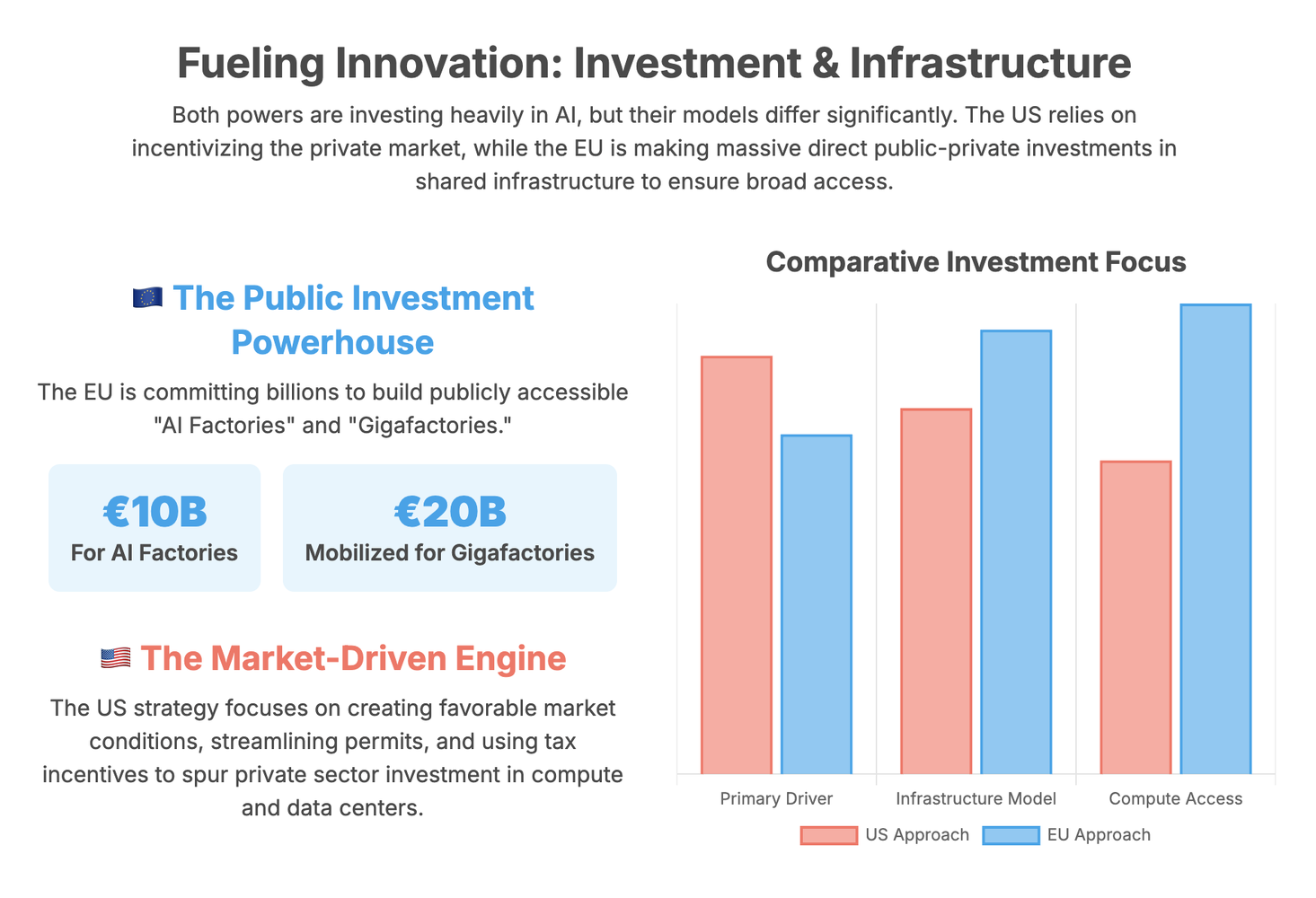

The EU's strategy for fostering AI innovation emphasizes "sustained investment in infrastructure (including computing power and networks), alongside advances in model development, and broad adoption across the economy".The EU aims for leadership "both in developing and using AI". A cornerstone of this approach is the deployment and scaling of "AI Factories," a network of supercomputers designed as dynamic ecosystems integrating AI-optimized supercomputers, large data resources, and human capital.This initiative involves a substantial EUR 10 billion investment (2021-2027) for 13 AI Factories, which will triple EuroHPC AI computing capacity.

Building on this, the EU plans to invest in "AI Gigafactories," large-scale facilities capable of training complex AI models with "hundreds of trillions of parameters" and "exceeding 100,000 advanced Al processors". The "InvestAI Facility" is set to mobilize EUR 20 billion for AI infrastructure, targeting up to 5 Gigafactories through public-private partnerships. The "Apply AI Strategy" is being launched to boost new industrial and scientific uses of AI and improve public services, with a focus on strategic sectors such as manufacturing, aerospace, and healthcare.European Digital Innovation Hubs (EDIHs) are being refocused to become "Experience Centres for AI" by December 2025, supporting AI adoption by SMEs, mid-caps, and public administrations.Furthermore, the "GenAI4EU initiative" provides financial support, allocating nearly EUR 700 million for applied research and the development of advanced AI models and solutions across various sectors.The "European AI Research Council (RAISE)" will pool resources for fundamental scientific advancements in AI and its application in science, supporting both "Science for AI" and "AI in Science".

Key Differences in Innovation Focus

A significant difference emerges in their approaches to providing compute infrastructure. The US primarily focuses on creating favorable market conditions by improving the "financial market for compute" and relying on "private-sector-led innovation" to ensure access to large-scale computing power for startups and academics. This reflects a belief that market mechanisms are the most efficient way to scale computing resources. In stark contrast, the EU is making massive direct public-private investments in shared, large-scale computing infrastructure like "AI Factories" (EUR 10 billion) and "AI Gigafactories" (EUR 20 billion mobilized by InvestAI Facility).These are designed to be publicly accessible and shared infrastructure. This difference reflects contrasting economic philosophies: the US trusts the private sector to build and provide compute resources, while the EU views high-performance computing as a strategic public good that requires significant state investment to ensure broad access and foster collective innovation, especially for smaller players and academia. This could lead to different competitive landscapes in AI, with the US potentially seeing larger, private hyperscalers dominate, while the EU aims for a more distributed and accessible compute environment.

Another distinction lies in how sectoral AI adoption is driven. The EU explicitly defines an "Apply AI Strategy" to accelerate AI adoption across specific strategic sectors (e.g., healthcare, manufacturing) and public administration, using instruments like European Digital Innovation Hubs (EDIHs).This suggests a proactive governmental role in driving AI integration. While the US also enables AI adoption through "regulatory sandboxes or Al Centers of Excellence", its emphasis is more on removing barriers and establishing testing environments, implying that adoption is largely a market outcome once conditions are favorable. The EU might achieve more widespread and targeted AI integration in critical sectors, potentially leading to greater overall societal benefits and economic resilience. The US approach relies more on the private sector to identify and implement adoption opportunities, which might be faster in some areas but less coordinated across the economy.

Finally, while both support open-source AI, their underlying motivations differ. The US encourages "Open-Source and Open-Weight Al" because it offers "unique value for innovation" for startups and academics and has "geostrategic value". This views open-source primarily as a tool for accelerating domestic innovation and maintaining competitive advantage. The EU also values open-source, but its broader context of "trustworthy AI" and "strategic autonomy" suggests it views open-source as a means to foster transparency, collaboration, and reduce dependencies on proprietary models, aligning with its values-first approach. Both support open-source, but their underlying motivations could lead to different policy implementations or preferred types of open-source projects. The US might favor projects that directly enhance its competitive edge, while the EU might prioritize those that foster broader ecosystem development and transparency.

Approaches to Building AI Infrastructure

US Infrastructure Plan: Deregulation, Energy Dominance, and Security

The US plan places a high priority on building "vast Al infrastructure and the energy to power it". A central tenet is "Streamlined Permitting for Data Centers, Semiconductor Manufacturing Facilities, and Energy Infrastructure".1 This involves aggressive reforms to environmental permitting, including establishing new Categorical Exclusions under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and expanding the use of the FAST-41 process. The administration explicitly states its intent to "continue to reject radical climate dogma and bureaucratic red tape" to facilitate rapid construction, encapsulated by the directive to "Build, Baby, Build!".Federal lands are also to be made available for data center and power generation construction.

The plan emphasizes developing an electricity grid that can "Match the Pace of Al Innovation".This involves stabilizing the current grid, optimizing existing resources, and prioritizing the interconnection of "reliable, dispatchable power sources" such as enhanced geothermal, nuclear fission, and nuclear fusion. Power markets are to be reformed to align financial incentives with grid stability.A significant focus is on restoring American semiconductor manufacturing, with efforts to remove extraneous policy requirements for CHIPS-funded projects and streamline regulations, while accelerating the integration of AI tools into manufacturing processes.Security is paramount, with directives to "Maintain security guardrails" to prevent adversaries from compromising infrastructure and ensuring the domestic AI computing stack is built on American products, free from foreign adversary information and communications technology and services (ICTS).1 Specific attention is given to building "High-Security Data Centers for Military and Intelligence Community Usage" and advancing the adoption of classified compute environments.1

European Infrastructure Plan: Public Investment, Sustainability, and Strategic Autonomy

The EU views computing power as "fundamental to Al model development all throughout the Al lifecycle", necessitating "sustained investment in infrastructure".1 A key initiative is the deployment and scaling of "AI Factories," which are dynamic ecosystems integrating AI-optimized supercomputers and large data resources within the EuroHPC network. This involves a EUR 10 billion investment (2021-2027) for 13 AI Factories, which will more than triple the current EuroHPC AI computing capacity.

The EU plans to further invest in "AI Gigafactories," large-scale facilities designed to develop and train complex AI models at an unprecedented scale, integrating massive computing power "exceeding 100,000 advanced Al processors".The "InvestAI Facility" aims to mobilize EUR 20 billion for AI infrastructure, targeting up to 5 AI Gigafactories across the Union through public-private partnerships. This initiative also seeks to "stimulate the design and in due course the manufacturing - of Al processors in Europe" to strengthen "strategic technological sovereignty".The "Cloud and AI Development Act" is proposed to incentivize large investments in cloud and edge capacity, aiming to at least triple the EU's data center capacity within five to seven years by simplifying permitting for resource-efficient projects.

Sustainability is a core requirement for EU infrastructure development. AI Gigafactories and data centers must consider "power capacity, as well as energy, water efficiency and circularity".A "Strategic roadmap for digitalisation and AI in the energy sector" will propose measures for the sustainable integration of data centers into the energy system, and an upcoming "Water Resilience Strategy" will focus on reducing their water footprint.1 For highly critical use cases, the EU emphasizes that "sovereignty and operational autonomy require highly secure EU-based cloud capacity".

Key Differences in Infrastructure Development

A notable difference lies in their approach to environmental regulation and its impact on infrastructure build-out. The US plan explicitly states a rejection of "radical climate dogma" and aims to "expedite environmental permitting by streamlining or reducing regulations". This indicates a willingness to prioritize rapid build-out over environmental concerns, viewing regulations as obstacles to speed and dominance. The EU, conversely, integrates energy and water efficiency, circularity, and sustainable integration into its infrastructure requirements for AI Gigafactories and data centers. It also plans a "Water Resilience Strategy" specifically to reduce the water footprint of these installations.This reflects a commitment to balancing technological advancement with environmental responsibility. The US approach might achieve faster infrastructure deployment, but potentially with higher environmental costs. The EU's integrated approach aims for more sustainable AI infrastructure, potentially setting a global standard for "green AI," but might face longer permitting processes despite simplification efforts.

Another distinction is the primary beneficiary and strategic framing of AI infrastructure. The US plan heavily emphasizes building high-security data centers specifically for "Military and Intelligence Community Usage" and prioritizing Department of Defense (DOD) access to computing resources during national emergencies.This positions AI infrastructure heavily as a strategic military asset. The EU's AI Factories and Gigafactories 1 are described as open to "industry, research, academia, and public authorities" 1 and crucial for "strategic industrial sectors".While dual-use applications are acknowledged, the primary focus is broader economic and scientific advancement. This difference in primary beneficiaries and strategic framing could lead to different types of AI capabilities being prioritized and developed. The US might see more classified or defense-specific AI infrastructure, potentially limiting broader commercial or academic access. The EU's more open, shared infrastructure model could foster wider civilian innovation and collaborative research, potentially leading to more diverse AI applications across its economy.

Furthermore, their approaches to energy supply for AI differ. The US links its energy strategy directly to AI dominance, emphasizing increased energy generation by "reject[ing] radical climate dogma and bureaucratic red tape".It focuses on stabilizing and optimizing the existing grid and bringing new power sources online rapidly.The EU also recognizes the energy challenge 1 but frames it within a "strategic roadmap for digitalisation and AI in the energy sector" that proposes measures for "sustainable integration of data centres" and "electricity grid optimisation".The US prioritizes raw energy capacity expansion, potentially through any means, to power AI. The EU, while also seeking capacity, emphasizes sustainable integration and optimization, reflecting its broader climate goals. This could lead to different energy mixes and grid development pathways for AI infrastructure.

Data Strategies

US Data Strategy: Scientific Datasets and Secure Federal Access

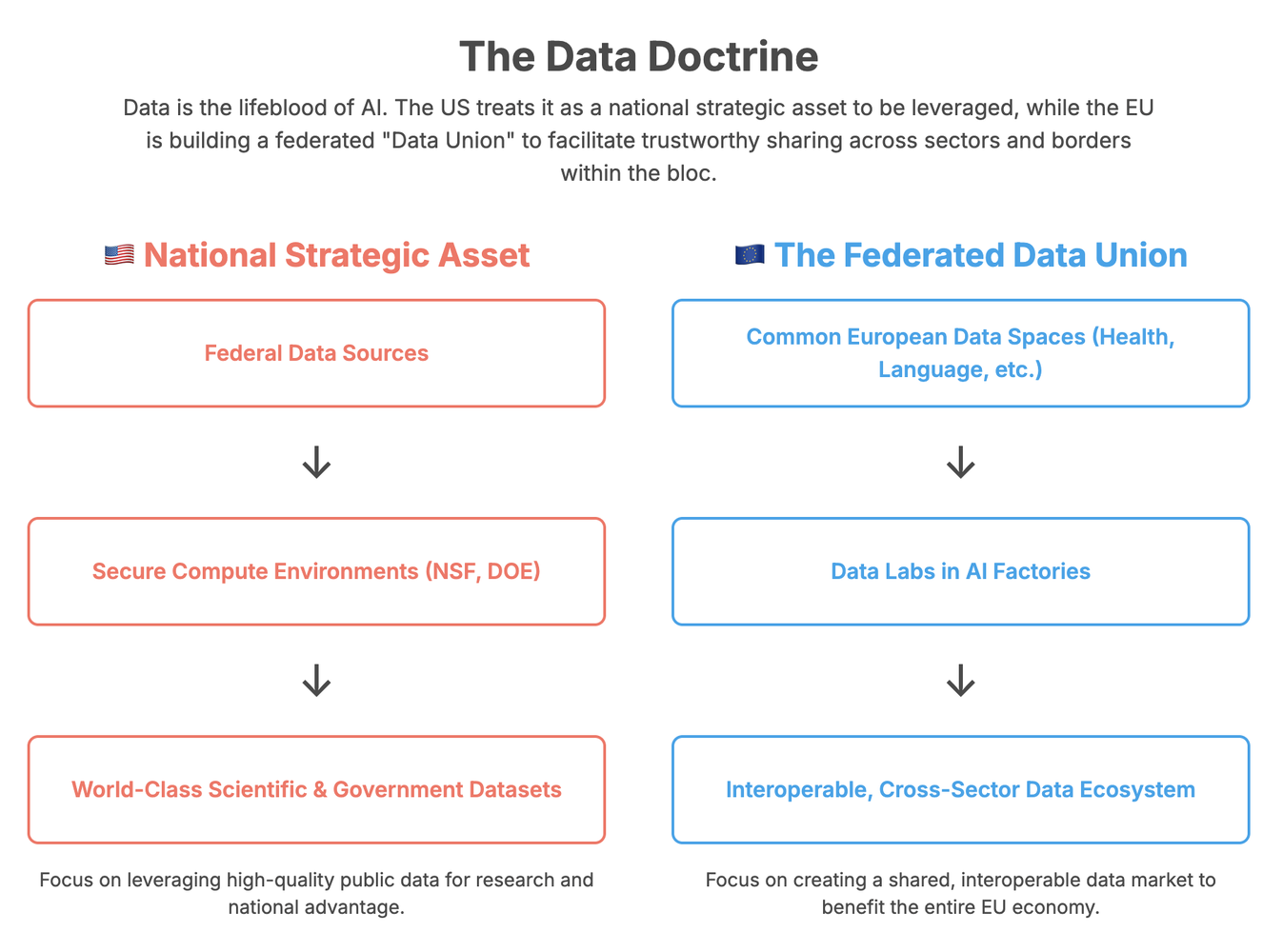

The US views "high-quality data" as a "national strategic asset", recognizing its critical role in achieving AI innovation goals. The strategy aims for the United States to "lead the creation of the world's largest and highest quality Al-ready scientific datasets".1 To ensure data quality, the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) Machine Learning and AI Subcommittee is directed to make recommendations on minimum data quality standards for various scientific data modalities used in AI model training.

A key aspect of the US data strategy involves leveraging federal data. This includes promulgating OMB regulations under the "Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act of 2018" to lower barriers and expand secure access to federal data, thereby facilitating AI use for evidence building while protecting confidential information.Secure compute environments are to be established within the National Science Foundation (NSF) and Department of Energy (DOE) to enable secure AI use-cases for controlled access to restricted federal data.1 An online portal for NSF's National Secure Data Service (NSDS) demonstration project is planned to provide public and agency access to such use-cases. Furthermore, federally funded researchers will be required to disclose non-proprietary, non-sensitive datasets used by AI models.A unique initiative involves exploring "the creation of a whole-genome sequencing program for life on Federal lands" to serve as a valuable resource for training future biological foundation models.

European Data Strategy: Data Union, Interoperability, and Trustworthy Sharing

The EU recognizes that "access to reliable and well-organised data is essential if the EU is to unlock the full potential of AI".To address the "scarcity of robust and high-quality data for the training and validation of Al models," the Commission plans to launch a new "Data Union Strategy" in the second half of 2025. This strategy will focus on "strengthening the EU's data ecosystem by enhancing interoperability and data availability across sectors".

A central component of this strategy is the establishment of "Data Labs" as integral parts of the AI Factories initiative. These Data Labs will "bring together and federate data from different AI Factories covering the same sectors" and link to "Common European Data Spaces".These labs are envisioned to offer a range of services, including cleaning and enriching datasets, providing technical tools (e.g., standardized formats, synthetic data), fostering interoperability, and offering data-pooling services while adhering to antitrust rules.The Commission is also supporting the development of "Simpl," a shared cloud software designed to "make it easier to manage and connect data spaces," thereby reducing technical complexity and costs.

Specific data pooling efforts include the "Alliance for Language Technologies (ALT-EDIC)," launched in March 2025, to build a comprehensive repository of high-quality language resources, aiming to break down language barriers and preserve Europe's linguistic and cultural diversity.1 In the health sector, the "European Health Data Space regulation" provides a common framework for securely making health data available for secondary use across the EU, contributing to reducing bias and enhancing fairness in AI applications.1 The "European Open Science Cloud" and Copernicus (geospatial data) also contribute to data availability for AI development.The Data Union Strategy also aims to streamline existing data legislation to "reduce complexity and administrative burden" and attract more valuable data while protecting sensitive EU data internationally. A public consultation on the Data Union Strategy is underway to gather stakeholder input.

Key Differences in Data Governance and Access

A key difference lies in the scope and approach to data availability. The US plan's data strategy is heavily geared towards building "world-class scientific datasets" and expanding "secure access" to federal data.1 This suggests a focus on specific, high-value datasets primarily for research and government use, with an emphasis on leveraging existing public sector data. The EU's "Data Union Strategy" aims for a broader vision of "interoperability and data availability across sectors" , with Data Labs linking AI Factories to Common European Data Spaces, encompassing diverse areas like health and language. This indicates a more ambitious and comprehensive approach to creating a federated data ecosystem that extends beyond public sources to include private sector data. The US approach might yield highly specialized AI models for scientific and government applications, but potentially less emphasis on broad, cross-sectoral data sharing for commercial AI development outside of these federal initiatives. The EU's strategy aims to unlock data for a wider range of commercial and public sector AI applications, potentially fostering a more diverse and integrated AI ecosystem across its economy.

Another distinction is how data is conceptualized and managed. The US frames data as a "national strategic asset", implying a focus on national control and competitive advantage. While it mentions "individual rights and ensuring civil liberties, privacy, and confidentiality protections", the emphasis is on securing and leveraging this asset for US dominance. The EU, while also recognizing data's value, emphasizes "fostering a trustworthy environment for data sharing" and "pooling data", with initiatives like Simpl and Data Labs designed to facilitate this. This suggests a view of data as a shared resource that, when made accessible and interoperable under robust safeguards, benefits the collective. This philosophical difference could lead to different approaches to data localization, cross-border data flows, and intellectual property rights related to data. The US might be more protective of its national data assets, while the EU might prioritize mechanisms that enable responsible data flow within its bloc and with trusted partners.

Furthermore, the EU's data strategy is explicitly driven by its values and societal needs. Its specific initiatives like the "Alliance for Language Technologies (ALT-EDIC)" for multilingual data and the "European Health Data Space regulation" are direct manifestations of its stated values of protecting cultural diversity and promoting human-centric AI. These initiatives are not just about data availability but about shaping AI to serve specific societal needs and preserve unique European characteristics. While the US mentions "whole-genome sequencing program" as a valuable resource, its data strategy details are less explicitly tied to its stated values of free speech or American values in the same granular, application-specific way. The EU's values-driven data strategy could set a precedent for how data is collected, shared, and utilized globally, emphasizing ethical considerations and societal benefit. This might influence international data governance norms, potentially creating a "European standard" for data sharing that prioritizes privacy, diversity, and public good, which could diverge from more purely commercial or national security-driven data strategies.

Workforce, Skills, and Talent Development

US Workforce Strategy: Worker-First, Retraining, and Infrastructure Focus

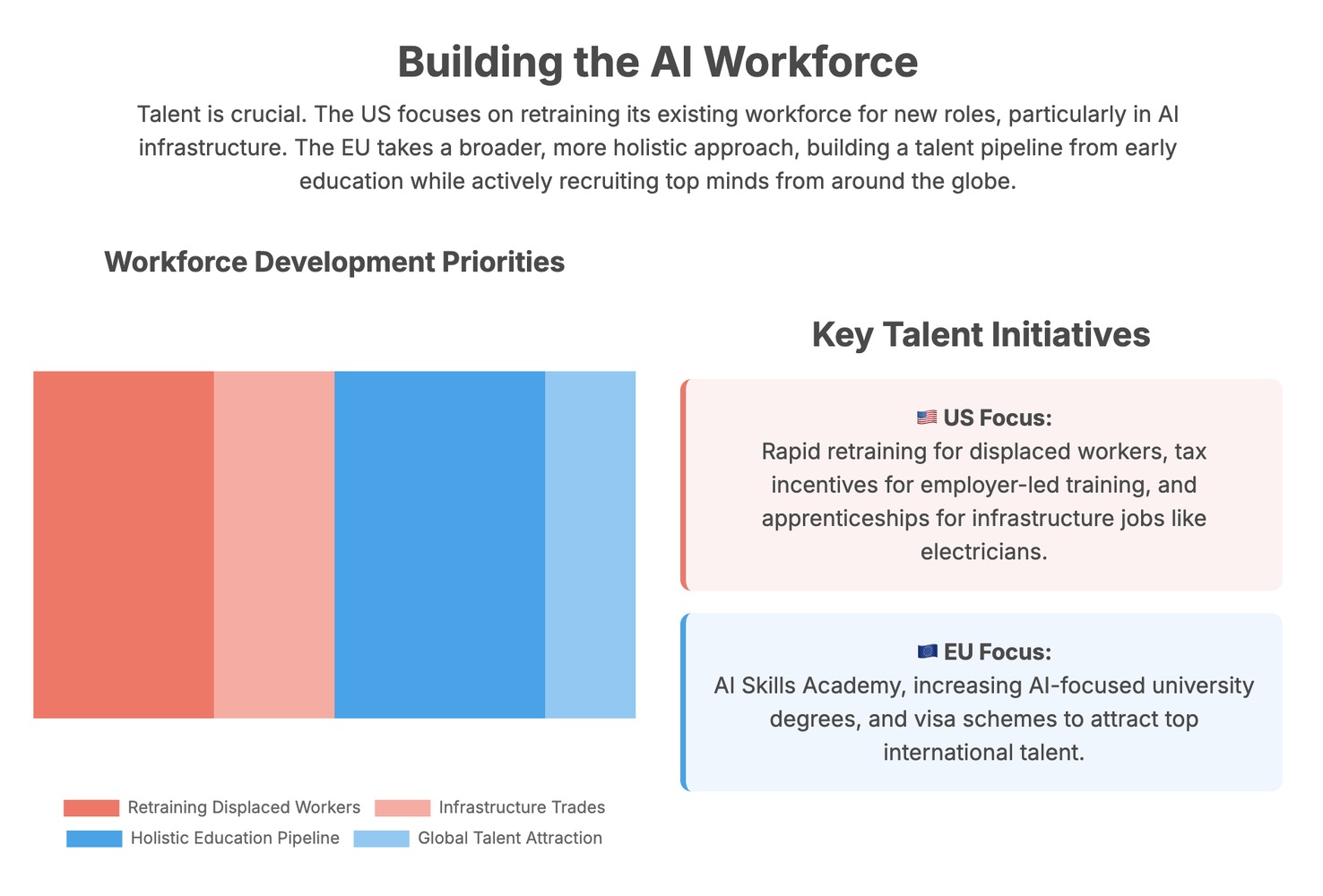

The US "America's AI Action Plan" prioritizes "Empower[ing] American Workers in the Age of AI", emphasizing a "worker-first Al agenda" where AI "complements their work-not replacing it".1 The strategy builds on existing executive orders, such as 14277 ("Advancing Artificial Intelligence Education for American Youth") and 14278 ("Preparing Americans for High-Paying Skilled Trade Jobs of the Future").It focuses on expanding "Al literacy and skills development" and continuously evaluating "Al's impact on the labor market".

The plan encourages employer-led training by clarifying that many AI literacy and skill development programs may qualify as tax-free educational assistance, enabling employers to offer reimbursement.The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and Department of Commerce (DOC) agencies are directed to study AI's impact on the labor market, including adoption, job creation, displacement, and wage effects, with an "Al Workforce Research Hub" under the Department of Labor (DOL) leading this sustained federal effort. Discretionary funding is leveraged for "rapid retraining for individuals impacted by Al-related job displacement", and new approaches to workforce challenges are piloted via states and workforce intermediaries.A significant component is training a skilled workforce for AI infrastructure, including electricians and advanced HVAC technicians. This involves a national initiative to identify priority occupations, develop skill frameworks, support industry-driven training, and expand early pipelines through general education, career and technical education (CTE), and Registered Apprenticeships.The DOE also expands hands-on research training at national laboratories, partnering with community colleges.

European Workforce Strategy: Holistic Education, International Talent, and Broad Upskilling

The EU emphasizes that Europe's "competitive strength lies in its people" and aims to address "talent shortages and cross-sectoral skill mismatches" in AI. The strategy seeks to "enlarge the EU's pool of AI specialists and to adequately upskill and reskill EU workers and citizens in the use of AI". This begins with high-quality and inclusive initial education, supported by the 2030 Roadmap on digital education and skills and its "AI in Education initiative," which promotes AI literacy for primary and secondary education and fosters ethical AI uptake.

The EU supports an increase in the provision of EU bachelor's, master's, and PhD programs focusing on key AI technologies, promoting them through virtual study fairs and scholarship schemes.A pivotal action is the launch of the "AI Skills Academy," a "one-stop shop providing education and training on skills related to the development and deployment of AI," with a focus on generative AI. The Academy will pilot an "AI apprenticeship programme" and offer "returnship schemes for female professionals".1 It also supports "AI fellowship schemes" to attract "highly skilled EU and non-EU PhD candidates as well as young professionals living outside the EU" to work in EU-based entities.To attract top international talent, the EU will implement measures in its "Visa Strategy" to improve directives for students and researchers, and pilot the "Marie Skłodowska-Curie action 'MSCA Choose Europe' scheme".The future "EU Talent Pool" and "Multipurpose Legal Gateway Offices" will further support attracting and retaining highly skilled non-EU workers, particularly in ICT. For broader upskilling and reskilling, European Digital Innovation Hubs will increase their skills and training services, offering hands-on AI courses for various profiles. The Commission also promotes AI literacy awareness and "AI for all" dialogue through dissemination activities.

Key Differences in Talent Development

A key difference in workforce development lies in the balance between reactive retraining and proactive pipeline building.

The US plan heavily emphasizes "rapid retraining for individuals impacted by Al-related job displacement" and continuously studying AI's impact on the labor market. This suggests a more reactive approach to the workforce changes brought by AI, focusing on adapting existing workers to new demands. The EU, while also addressing upskilling and reskilling, places significant emphasis on building a future pipeline of AI specialists from early education, through its "AI in Education initiative" and by increasing the provision of AI-focused degrees.The EU's long-term investment in structured education and programs could create a more robust and sustainable AI talent base over time, potentially giving it a competitive advantage in foundational AI research and development, whereas the US might see quicker, more ad-hoc responses to immediate industry needs.

Another significant divergence is the focus on domestic versus global talent attraction. The US plan explicitly states a "worker-first Al agenda" and focuses on "American workers", with initiatives like tax-free reimbursement for training aimed at "preserving jobs for American workers".While it seeks "world-class scientific datasets," its talent focus is primarily domestic. The EU, while also supporting its own citizens, has explicit and detailed strategies for "attracting and retaining skilled Al talent from non-EU countries" through various visa schemes, AI fellowship schemes, and talent pools. This more open and structured approach to international talent attraction could make the EU a global hub for AI researchers and practitioners, potentially accelerating its innovation capabilities by drawing from diverse expertise, whereas the US approach might foster a strong domestic AI workforce but could limit its access to the broader global talent pool.

Finally, the scope of skills development differs. The US plan specifically identifies and prioritizes "high-priority occupations essential to the buildout of Al-related infrastructure" like electricians and advanced HVAC technicians, expanding apprenticeships in these areas.This shows a direct link between AI and tangible infrastructure needs. The EU, while also addressing specialist skills through its AI Skills Academy, additionally focuses on broad "AI literacy" for "all" citizens and the wider population.1 This aims to create a more AI-aware and adaptable society, which could lead to broader AI adoption and more informed public discourse around AI's societal implications, complementing the US's more targeted approach to a practical workforce for AI infrastructure. The EU's explicit inclusion of "attracting more women to AI" and "returnship schemes for female professionals" also demonstrates a clear commitment to diversity and inclusion in AI talent development that is not explicitly mirrored in the US plan.

International Diplomacy and Security Strategies

US International Strategy: Global Dominance, Countering Adversaries, and Export Controls

The US aims to "Lead in International Al Diplomacy and Security" , driven by the objective to "drive adoption of American Al systems, computing hardware, and standards throughout the world".A key component is to "Export American Al to Allies and Partners," ensuring that allied nations build on American technology and join "America's Al alliance".

The strategy explicitly targets geopolitical rivals, focusing on "Counter[ing] Chinese Influence in International Governance Bodies". The US intends to "vigorously advocate for international Al governance approaches that promote innovation, reflect American values, and counter authoritarian influence".A significant emphasis is placed on "Strengthen[ing] Al Compute Export Control Enforcement" by exploring location verification features on advanced AI compute and collaborating with Intelligence Community (IC) officials on global chip export control enforcement. Efforts are also directed at "Plug[ging] Loopholes in Existing Semiconductor Manufacturing Export Controls" by developing new controls on sub-systems to prevent adversaries from leveraging US innovations.The US seeks to "Align Protection Measures Globally" with partners, indicating a willingness to use tools such as the Foreign Direct Product Rule and secondary tariffs if allies do not follow US controls or "backfill".A technology diplomacy strategic plan for an "Al global alliance" will be developed to align incentives and policy levers globally.

On the security front, the US government aims to be at the forefront of "Evaluating National Security Risks in Frontier Models," particularly concerning cyberattacks and the development of chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or explosives (CBRNE) weapons, as well as novel security vulnerabilities. The plan also includes specific actions to "Invest in Biosecurity" to screen for malicious actors and prevent the synthesis of harmful pathogens, requiring federal funding recipients to use robust nucleic acid synthesis tools and facilitating data sharing for screening.

European International Strategy: Global Governance, Trust, and Digital Partnerships

The EU views "International engagement" as an "integral part of the strategy" to strengthen its global position and influence in AI.The EU seeks to "lead global efforts on Al by supporting innovation, ensuring trust through guardrails, and developing the global governance on AI".This is pursued through "proactive bilateral and multilateral engagement with partner countries".

A core objective is to "join efforts with like-minded partners, candidate and potential candidate countries, to promote a safe, trustworthy and human-centric AI development in multilateral fora".The EU aims to explore the potential of its "digital partnerships and international digital cooperation" to promote an AI approach that "enhances human well-being and societal progress".1 An upcoming "Communication on International Strategy for Digital Sovereignty, Security, and Democracy" (Q2 2025) will further elaborate on the EU's international approach.

Key Differences in Global Engagement

A significant difference lies in their geopolitical framing: confrontational competition versus collaborative governance.

The US strategy is explicitly designed to "counter Chinese influence" and focuses on "Denying our foreign adversaries access" 1 to advanced AI compute and semiconductor manufacturing. It is willing to use strong tools like export controls and secondary tariffs to enforce its will on allies. This indicates a confrontational, power-projection approach to international AI. The EU, while also aiming for leadership, emphasizes "leading global efforts on Al by...developing the global governance on AI" through "proactive bilateral and multilateral engagement" and "joining efforts with like-minded partners".This is a less confrontational, more values-driven approach to global governance. The US approach risks fragmenting the global AI landscape into competing blocs, potentially escalating tech-based geopolitical tensions. The EU's approach aims for a more unified global framework based on shared values, potentially fostering broader international consensus but perhaps slower to achieve concrete outcomes.

Another distinction is the primary means of building global influence: technology export versus values export. The US seeks to "Export American Al to Allies and Partners" to build an "America's Al alliance".This suggests that the diffusion of American technology is a primary means of building influence and securing partnerships. The EU aims to "promote a safe, trustworthy and human-centric AI development" in multilateral fora, implying that its regulatory and ethical model is its primary export for global influence. The US might gain market share and technological alignment among its allies, but could face pushback if its technology comes with political strings. The EU's "Brussels effect" could lead to its regulatory standards becoming de facto global norms, but might be less effective in directly competing on raw technological deployment speed.

Finally, their focus on specific security threats differs. The US plan explicitly focuses on evaluating "national security risks in frontier models" related to "cyberattacks and the development of chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or explosives (CBRNE) weapons" , and invests in biosecurity to screen for malicious actors.1 This highlights a direct, threat-centric security focus on existential risks posed by advanced AI capabilities in the hands of malicious actors. The EU's international strategy mentions "enhancing human well-being and societal progress" 1 as a goal for its AI approach, which, while encompassing security, frames it within a broader human-centric context. The US will likely prioritize security measures that directly counter state-level threats and proliferation risks. The EU's broader focus might lead to more comprehensive but perhaps less immediately targeted security measures, with a greater emphasis on ethical guidelines and human rights in its international engagements.

The comparative analysis of the US "America's AI Action Plan" and the EU "AI Continent Action Plan" reveals two distinct, yet equally ambitious, visions for AI leadership. The United States champions a model of rapid innovation driven by private sector freedom and deregulation, with a clear focus on achieving global technological dominance and bolstering national security.

Its approach to governance is largely reactive, seeking to remove perceived barriers to innovation, and its infrastructure and data strategies are often linked to military and scientific applications, with less explicit emphasis on environmental integration. Workforce development is framed around complementing American jobs and providing rapid retraining for displacement. Internationally, the US adopts a competitive stance, actively countering adversaries and leveraging technology exports to build alliances.

European Union's strategy is fundamentally rooted in a values-first approach, prioritizing trustworthy and human-centric AI that safeguards democratic principles and cultural diversity. Its governance model is proactive and comprehensive, centered around the AI Act, which aims to create a harmonized single market for responsible AI.

The EU commits substantial public-private investments in shared AI infrastructure, with a strong emphasis on sustainability and strategic autonomy in critical technologies like semiconductors. Its data strategy is geared towards creating an interoperable "Data Union" across sectors, fostering widespread data sharing under robust safeguards. Workforce development is holistic, focusing on building a deep talent pipeline from early education and actively attracting international expertise. Globally, the EU seeks to lead through multilateral engagement and normative influence, promoting its ethical AI model and digital partnerships.

These differences are not merely stylistic; they represent fundamental divergences in political philosophy, economic models, and societal priorities. The US's emphasis on speed and dominance, achieved through deregulation and market forces, could lead to rapid technological advancements but potentially at the cost of broader ethical alignment or social equity. The EU's commitment to trust, values, and strategic autonomy, while potentially slower in raw innovation speed due to regulatory overhead, aims to build a more resilient, inclusive, and globally influential AI ecosystem. The long-term implications of these divergent paths will shape not only the future of AI development but also the geopolitical balance of power and the global standards for responsible technological governance.

Attribution: This research was conducted with the assistance of an AI model to facilitate the extraction, synthesis, and comparative analysis of information from the provided US and EU AI policy documents. The AI's role was to process and organize complex textual data to support the human-driven analysis and conclusions. While every effort was made to ensure clarity and accuracy, any interpretations or strategic reflections are solely my own.

Author: Dimitris Dimitriadis

Have a paper, report, or insight worth sharing?

Send it to info@dcnglobal.net for a chance to be featured on the DCN Global Blog. We’re always looking to highlight fresh perspectives from our community!